Music Of Light – Conducted by

Dr Darren Postema

Indulge your senses at ‘Music of Light’, as Lismore Symphony Orchestra, joined by The Murwillumbah Philharmonic Choir and organist Warren Whitney, present a captivating concert of classical music from the intense emotions of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture to the pure joy of Mozart’s Church Sonata in C and the tranquil radiance of Rutter’s Beauty of the Earth.

Marvel at the exquisite architecture as the music soars through the beautiful St Carthage’s Cathedral in an afternoon of music sure to illuminate the spirit and delight the soul.

2 pm Sunday April 7, 2024

St Carthage’s Cathedral

8 Leycester St, Lismore

Programme notes

The Composer

Patrick Doyle (b.1953) is an award winning Scottish composer renowned for his scores written for numerous iconic films spanning the 20th and 21st centuries. With a portfolio boasting over 60 film scores, Doyle’s creative journey began as a young tuba player in the Conservatoire of Scotland’s junior orchestra at the age of 17.

His passion for composition led him to the Royal Scottish Academy of Music, graduating at 22 years old, and culminating in his appointment as a Fellow in 2001.

Doyle ventured into acting during the mid-seventies, gracing screens in notable productions such as Chariots of Fire and Much Ado About Nothing, for which he also composed the score, under the direction of Kenneth Branagh.

He joined Branagh’s theatre company in 1987 and composed music for their plays. In a pivotal moment in 1989, Doyle’s collaboration with Branagh on the film Henry V yielded the stirring anthem ‘Non Nobis Domine’, earning him the prestigious Ivor Novello Award for Best Film Theme. Continuing to work with Branagh, his versatility shone as he continued to traverse genres, crafting the scores for a diverse array of fourteen films, including Thor, Cinderella and Death on the Nile. Films he has scored for other directors include Bridget Jones’ Diary, Sense and Sensibility and, collaborating with Mike Newell, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

With an enormous show of determination, he wrote the score for Quest for Camelot in hospital while receiving treatment for leukaemia in 1989. He made a full recovery.

His ‘outstanding achievements and contributions to the world of film and television music’ were recognised in 2013 with the ASCAP Henry Mancini Award, a testament to his enduring impact on the industry.

The Music

‘Non Nobis Domine’, is a biblical prayer of gratitude for some great achievement which avoids the sin of pride by ascribing the credit to God, the phrase coming from Psalm 113:9. It was put to music during the Renaissance and was referred to in Shakespeare’s 1599 play of Henry V when the King proclaims it be sung after their victory at the Battle of Agincourt. It evolved into a three part canon that came to be sung at Grace in several British schools.

Doyle’s composition for the 1989 film builds from a gentle beginning to a triumphant crescendo, encapsulating the essence of humility and divine praise.

Non nobis Domine, Domine,

Non nobis Domine,

Sed nomine, Sed nomine,

Tuo da gloriam

Not unto us, O lord,

Not unto us, O lord,

But to Your name, But to your name

May all the glory be

Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt

The Composer

John Rutter (b.1945) stands as a revered English composer and conductor, celebrated particularly for his contributions to choral music, and he continues to conduct numerous orchestras and choirs worldwide.

His desire to become a musician from a very early age was nurtured at his nursery school (where he sang very loudly with the other kids), and by experimenting on his non-musical parents’ honky-tonk piano. He eventually began piano lessons at the age of seven, and his teacher, recognising his talent, encouraged him to become a composer or singer (rather than a pianist!).

At Highgate School for Boys, noted for its musical legacy, he relished participating in the choir which was directed by the gifted composer, Edward Chapman. His trajectory continued at Clare College, Cambridge, where he met the director of King’s College Choir, Sir David Willcocks, with whom he created four volumes of the successful ‘Carols for Choirs’ anthology while still a student. Willcocks recommended Rutter’s compositions to the Oxford University Press who signed him up in a partnership that endures to this day.

For four years from 1975, he directed the choir of Clare College, Cambridge, then in 1981, established his own choir, the Cambridge Singers, with whom he has recorded many albums under his own label, Collegium Records.

Tragically, he suffered with M.E. (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) from 1985-1992, and from the loss of his teenage son, Christopher, who was struck by a car in 2001. Rutter could barely compose for two years until he was inspired to create his ‘Mass of the Children’ after recollecting his participation in Benjamin Britten’s ‘War Requiem’, conducted by Britten himself, while still at school, and how enriching it had been to perform with professionals.

His music displays influences from French and English choral traditions, American classic song writing and light music. Light music consists of shorter classical orchestral pieces that are continuous, non-sectional and non-repetitive. They appeal to a wider audience and in different contexts for example, for radio. The style originated in the 18th century reaching its height of popularity in the mid-twentieth century with examples including Elgar’s ‘Salut d’Amour’ and Coates’ ‘The Dam Buster’s March’. Not restricted to shorter pieces, his larger scale works include ‘Gloria’, ‘Requiem’ and ‘Magnificat’, and he wrote beautiful instrumental music such as ‘Suite Antique’ for the flute.

His works have been commissioned for such illustrious occasions as the Gold and Platinum Jubilees of Queen Elizabeth II as well as the weddings of William and Kate, and Charles and Camilla.

His prestigious honours include a CBE awarded in 2007, a Lambeth Doctorate of Music from the Archbishop of Canterbury for his contribution to church music, and in 2023, Fellowship of The Ivory Academy, the highest honour possible, joining the likes of Kate Bush CBE and Sir Elton John.

The Music

‘For the Beauty of the Earth’ is a sacred choral composition based on the first four stanzas of the 1864 hymn by Folliott Sandford Pierpoint, the English poet and hymn writer born in 1835. It was inspired while he was contemplating the idyllic countryside near the City of Bath, stirring a sense of gratitude for the earth’s beauty and the joy of human love.

Rutter directs the orchestra to play happily, the piece starting with dainty broken chords from the flutes and harp, weaving a tapestry of rich textures and harmonies throughout and includes a counter melody in the third stanza. The lyrics celebrate the wonders of nature – trees, flowers, stars and moon – and the joy brought by cherished friends and relatives.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, born in 1756 in Salzburg, Austria, lived a tragically short 35 years. A child prodigy, he became arguably the most famous composer of all time, yet despite his musical genius, he often faced financial hardship. The day of his modest church funeral was marred by bad weather and was only sparsely attended. Belying the magnitude of his legacy, he was buried in an unmarked grave, the location of which was soon forgotten.

Under the tutelage of his father Leopold, Mozart’s musical education began at an early age. By five, he displayed remarkable proficiency on the clavier and violin, with his first compositions transcribed by his father. Embarking on a European tour at six, accompanied by Leopold and his gifted sister Nannerl, Mozart astounded audiences with his precocious talent. He met the future Queen of France, Marie Antoinette, when they were both just seven years old.

While touring Italy, a popular story arose after the fourteen year old heard Allegri’s Miserere at the Sistine Chapel. Leopold wrote to his wife: ‘You have often heard of the famous Miserere in Rome, which is so greatly prized that the performers in the chapel are forbidden on pain of excommunication to take away a single part of it, to copy it or give it to anyone. But we have it already. Wolfgang has written it down’.

Despite his impulsive nature and occasional tactlessness, Mozart endeared himself to peers and patrons alike, his affability belying his financial ineptitude and singular devotion to music.

At just sixteen years old, Mozart was employed as cathedral organist and composer for the Archbishop of Salzburg from 1772-1781. He took a two-year break after he resigned in 1777 during which he found himself struggling to make a living, and was greatly affected by the death of his mother in 1778. Despite his dissatisfaction with the Archbishop due to the creative constraints imposed and his resentment at being treated like a servant, he was very productive. He composed symphonies, sonatas, string quartets, masses, serenades and a few minor operas. His five violin concertos led to him receiving Europe-wide recognition with the last three forming part of the standard repertoire today. It was while he was employed there that he also composed the ‘Church Sonatas’.

After a dramatic final resignation where Mozart was literally kicked out of the door, he settled in Vienna, finding creative freedom after his break from the Archbishop’s constraints on his artistic expression. His compositions took on an individual character marked by a refusal to conform to public tastes when he wished to express something dear to him. Leopold, however, urged him to prioritise composing lighter, more commercially viable music in order to afford a living.

In 1782 he married Constanze with whom he later had 6 children, only two surviving past infancy. She was the sister of Aloysia Weber, his first unreciprocated love, but despite Constanze’s musicality and beautiful voice, they had nothing in common except their mutual struggle to manage money.

Following his father’s death in 1787, Mozart’s financial woes deepened, forcing him to pawn belongings and solicit loans from friends. Despite these challenges, his creative output remained prolific, yielding masterpieces like ‘The Magic Flute’ and the ‘Clarinet Concerto in A’.

In the months leading up to Mozart’s untimely demise, he grappled with failing health, convinced he was being poisoned. He was still writing the ‘Requiem Mass’ on the day he died. Commissioned by a mystery nobleman, he had often remarked that he was writing it for himself.

The Music

Mozart wrote a total of seventeen Church Sonatas from 1772-1780 while he was in the employ of the Archbishop of Salzburg. The LSO will play the 16th of these sonatas, ‘K.329 in C major’, written in 1779 for organ and orchestra.

The sonatas were intended to be performed during a musical mass and were short in length to suit the time required when the celebrant changed position from one side of the choir to the other, between the readings of the Epistle and the Gospel. Most of the sonatas were scored for organ and two violins, but three have a much larger orchestration than the others, the K.329 having the largest. It is thought that it was composed for the same service as the renowned Coronation Mass.

The ‘Church Sonata in C major, K.329’ consists of only one movement, a lively allegro. The piece is full of joy and grandeur alternating with more delicate moments from the violins.

The Composer

During the Baroque period, Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) became one of the most significant composers that ever lived, yet devastatingly, his life ended in poverty despite his immense contributions to music. His works were almost forgotten until their rediscovery in the 20th century. Best known for his masterpiece ‘The Four Seasons’, Vivaldi’s repertoire also includes a series of violin concertos that pushed the boundaries of technical skill. Deviating from the classical style initiated by Corelli, he developed the concerto form, influencing his contemporary, the great J.S. Bach (1685-1750).

Taught by his professional violinist father in Venice, Vivaldi’s early education in music paved the way for his prodigious talent. Ordained as a priest after 10 years of study, he didn’t enter the church due to an exemption given because of his ‘tightness of chest’. At 25 he found his calling as a violin teacher, and eventually choir master, at the Ospedale della Pieta, a refuge for orphaned girls. Here he composed numerous concertos, cantatas and sacred vocal works for the institution’s renowned choir and orchestra, showcasing his versatility and innovation. From 1705 collections of his works began to be published and earned him recognition and commissions across Europe.

Despite intermittent clashes with the board and his subsequent dismissal in 1709, he was unanimously voted back in two years later with his responsibilities expanding to include the monthly composition of multiple concertos. He ventured into opera composition on the side as it was the most popular genre of musical entertainment at the time, and despite facing mixed reception due to his progressive style, he wrote 50 operas.

Around 1718, a sojourn in Mantua under Prince Philip’s patronage saw Vivaldi produce notable operas and instrumental works, including the famed Four Seasons. Pioneering a novel approach to music, his compositions were inspired by and reflected the Italian landscape and culture. He subsequently visited Milan and Rome before returning to Venice in 1725.

As the years passed, however, Vivaldi’s music faded from public consciousness, and financial difficulties plagued his later life. His passing in obscurity, attended by a scant few mourners, belied the enduring impact of his compositions.

The Music

It was during his time in Mantua in 1720, inspired by the surrounding countryside, that Vivaldi composed the ‘Concerto for Two Cellos in G minor’.

In its first movement, the soloists engage in virtuosic interplay, eschewing the typical orchestral introduction for a dynamic dialogue. The motif of ‘swarmers’, the rapid reiteration of four notes reminiscent of buzzing bees, recurs throughout, echoing themes from ‘The Four Seasons’. The Largo offers a solemn trio sonata with the continuo cellist playing the third part, while the final allegro bursts forth with syncopated energy, showcasing the soloists’ musical prowess. The orchestra will be performing the first movement.

The Composer

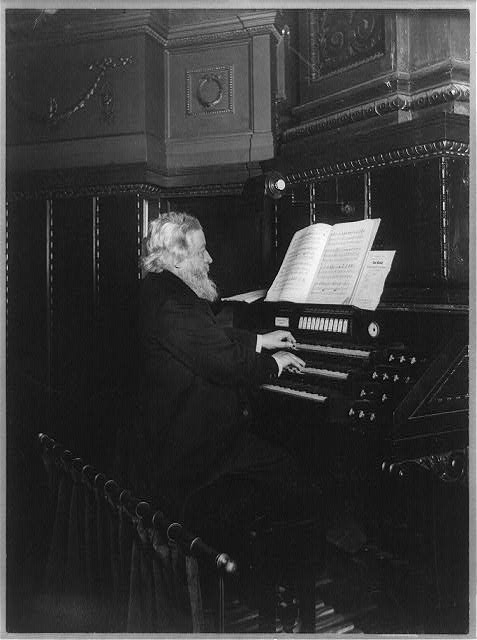

Guilmant (1837-1911) emerged as the foremost French organist during an era when music thrived in Paris, with concerts held in unconventional venues like department stores and the zoo.

Under his father’s tutelage and later, at 23, with Belgian master Lemmens, Guilmant honed his organ skills. At 34, he assumed the organist position at La Trinite church in Paris, a tenure spanning 30 years. He married Louise Bleriot in 1865 and raised four children.

Renowned for his improvisational prowess inspired by Gregorian chants, Guilmant achieved international acclaim, becoming the first major French organist to tour the USA. He was also bestowed the honorary title of organist at Notre-Dame de Paris, further solidifying his global influence.

A prolific composer, Guilmant crafted a vast organ repertoire, demonstrating mastery of orchestral scoring and dynamics. His concerts, featuring themed programmes with diverse repertoire, resonated widely. He published several important collections of organ scores and played a pivotal role in promoting J.S. Bach’s organ compositions as the cornerstone of organ training.

Guilmant’s unique perspective emphasised the organ’s distinctiveness from the orchestra, advocating for its noble tone quality and emphasising its inherent richness, contrasting with approaches that sought to mimic orchestral sounds. He co-founded the Schola Cantorum in 1894, providing an alternative to the Paris Conservatoire’s opera- centric curriculum. The kindness and detail with which he taught were remarked upon, and he taught there until his death.

The Music

While rooted in baroque tradition and religious music, Guilmant’s ‘First Symphony for Organ and Orchestra’ transcends its origins with a romantic, lyrical, and spirited composition spanning three movements. The influence of Beethoven is unmistakable, particularly in the first two movements, while reflecting Guilmant’s own distinctive style and musical vision.

The opening movement features a commanding solo executed solely with the foot pedals, leading into two distinct themes—one vibrant and energetic, the other imbued with romance. The delicate Pastorale of the second movement captivated audiences, prompting an immediate encore at the symphony’s 1878 premiere. The grand finale showcases Guilmant’s virtuosic skill, beginning with a neo-Baroque toccata filled with rapid runs and contrasting melodies. A lyrical chorale emerges, building to a majestic procession before culminating in a triumphant maestoso conclusion. The orchestra will perform the third movement.

The Composer

Chris Gleeson (b.1960) is an Australian composer with an unwavering dedication to his pursuit of excellence in violin playing and his commitment to academic achievement.

Chris Gleeson’s musical life began with guitar lessons at 10 years of age. He soon graduated to playing in church and performing in a successful rock band. He started violin lessons after meeting former Sydney Symphony Orchestra violinist, Gwyneth Grant, during his HSC year.

A scholarship to Sydney Conservatorium led to tertiary violin studies at Newcastle Conservatorium where he gained his Diploma of the State Conservatorium of Music (DSCM) in performance. He was awarded a violin scholarship in 1986 with the ABC Sinfonia, a training ground for post- graduate musicians to enter the state orchestras.

Following a stint with the Australian Opera and Ballet Orchestra, a professional orchestra owned by Opera Australia, he became a long-term member of the Willoughby, Hunter, East West and Wollongong orchestras. For 14 years he ran a string quartet for Sydney Music Enterprises and worked with the Tommy Tycho Orchestra and several groups including: The Goat Band, The Rum Culls, Ethnic Jazz and others.

He studied piano as a second instrument and also worked as a piano accompanist for Sydney musical productions.

Chris began saving compositional sketches, ideas that he could not resist the temptation to write down, from his DSCM years. After gaining encouragement about his first violin concerto from leading Australian composer Matthew Hindson, he decided to pursue composition more seriously around 2010. Regarding his compositional method, Chris relates that he needs to have an idea come to his mind that seems to have potential and is a little obsessive, then he knows it is time to work.

His plethora of qualifications also include a Graduate Diploma in performance from The Australian Institute of Music, Master of Teaching from Sydney University, Bachelor of Music with Honours from The University of New England in 2015, and Master of Music in composition from The Australian National University in 2018. His most recent degree is a Master of Philosophy in music composition from The University of New England.

The Music

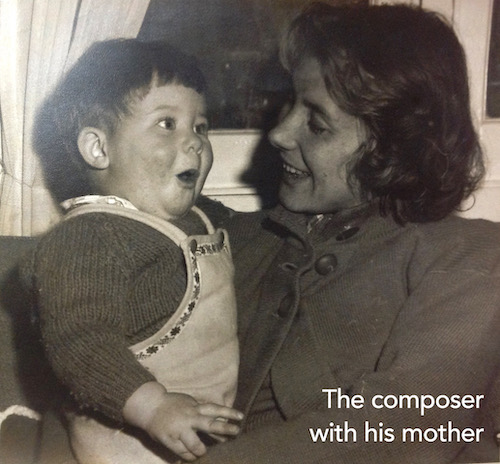

‘Remembrance’ is a tribute to the life and personality of my mother, Mrs. Beverly Thomson, who died of cancer at age 87 years on November 22nd 2022. It is also a prayer for all those who have experienced the grief that comes with the loss of a loved one.

‘Remembrance’ employs an arching ABA musical form with each main section containing a number of developmental variations and sub-themes. The two main themes, A and B, reflect two dominant aspects of the personality of the deceased; the loving and nurturing mum and the forthright social contributor/family manager.

The different instrumental families of the orchestra highlight these contrasting aspects of personality with the brass, for example, portraying strident confident characteristics. The strings engage in both expressive legato and more playful moments.

The opening A themes are wistful, like memory itself, especially when one is emerging from a period of grief and beginning to experience moments of what might be called, ‘joyful sadness’, where loss is accepted and the beauty of the deceased respectfully recalled.

The piece begins in a tentative E flat major but modulates to G major as nostalgic recollections begin to emerge. The B subject is in the brass. It is in G minor and bold in character. The climax is marked by an orchestral tutti making a resounding return to E flat major. Some chromatic modulation and more playful variations resolve with a return of the A theme to finish in E flat major.

May God rest her soul – Christopher Gleeson

The Composer

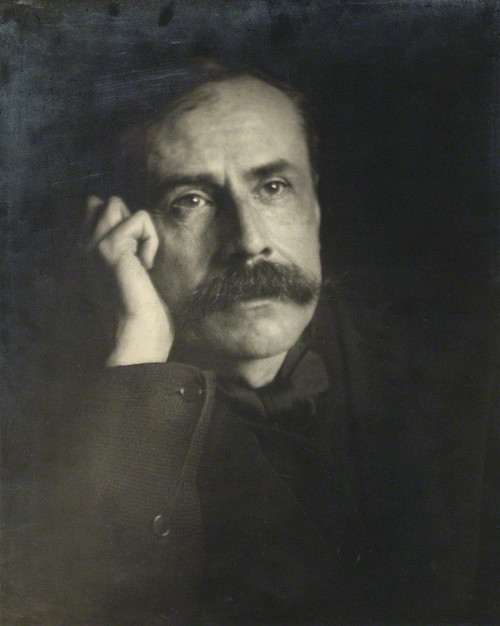

Sir Edward Elgar’s (1857-1934) journey from a largely self-taught musician to one of England’s greatest composers, underscores the power of love and determination over a formal education.

Born into a musical family and receiving piano lessons at an early age, he was determined to pursue a musical career, despite his father’s reluctance for him to do so. He taught himself to play the instruments in his father’s music shop in Worcester, and at 16, lacking formal training and financial means, Elgar continued his self-education by playing instruments in small orchestras and learning to conduct. He had no training in theory whatsoever, but by 20 he could afford some violin lessons in London, then landed his first professional music job as bandmaster at the Worcester County Pauper and Lunatic Asylum in 1879.

At 23, Elgar devoted himself to composition, but it was at 32, upon marrying Caroline Alice Roberts, 9 years his senior, and for whom he had composed his ‘Salut d’Amour’ as an engagement gift, that he found the confidence and unwavering support he needed. Alice, a published author, provided the understanding and guidance he needed to flourish, freeing Elgar from the self-doubt that had stifled him. His unique path allowed him to gain an unparalleled mastery of the orchestra.

Elgar’s compositions, influenced by Wagner and Brahms yet distinctly original, captured the essence of the English landscape that he dearly loved. His meticulous orchestration and heartfelt melodies resonated deeply with audiences and he devoted himself to making his compositions understood by the musicians playing them. His breakthrough came with the performance of the ‘Enigma Variations’ in London in 1899.

Following their success, Elgar’s reputation grew with his oratorio ‘The Dream of Gerontius’, especially after its performance in Germany which earned him recognition across Europe. England, realising that for the first time in 200 years, they had a composer of world stature, showered him with awards including a knighthood at Edward VII’s coronation.

From 1900-1920, Elgar produced his most significant works: ‘Pomp and Circumstance’ and the ‘Cello Concerto in E minor’. Heart-wrenchingly, his beloved wife died in 1920 and he could produce nothing more of note.

The Music

Elgar explained how the ‘Enigma Variations’ came to be written:

‘One evening after a long tiring day, I lit a cigar and sat down at the piano. A theme came to me. My wife looked up and asked “What is that?”. “Nothing,” I replied, “but perhaps it can be made into something.”’ He continued to play amusing variations on the theme each representing a characteristic of their friends. He composed 14 variations in 14 days.

Nimrod, the ninth variation, paid homage to his new friend and music publisher, Auguste Jaeger, whose surname is German for ‘hunter’. Nimrod was the name of a great hunter from the Bible. It affectionately represents Jaegar giving an elegant lecture on the slow passages in Beethoven on a beautiful summer afternoon. The opening resembles the Adagio of the ‘Pathetique Sonata’.

The enigma lies in the identity of a well-known, but unplayed tune to which Elgar’s theme serves as a counterpoint, a mystery Elgar took to his grave.

The Composer

Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), the Russian composer, stands as a beacon of resilience for those who have faced skepticism about their abilities. Despite enduring criticism and grappling with his own self-doubt, he pursued his musical calling with unwavering determination, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire generations.

From his earliest years, Tchaikovsky harboured a profound passion for music, though his academic prowess failed to impress, with even his piano teacher discouraging him from pursuing a musical career. His dreamy disposition and sensitive nature often found solace in the melodies that danced through his mind. He was so enamoured by music that he’d wake up in the middle of the night exclaiming ‘Can you hear the music?’.

Determined to follow his passion, Tchaikovsky abandoned his clerical job at 23 to enrol in the St. Petersburg Conservatory. Despite his fervent dedication, even writing 200 variations on a given theme in one night, his compositions initially faced harsh criticism. Amidst the disapproval, glimpses of his potential shone through as noted by discerning critics like Laroche, who foresaw Tchaikovsky’s pivotal role in Russia’s musical future.

His early works encountered lukewarm reception, including the initial rendition of the ‘Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture’ (1870), now hailed as a masterpiece of Russian classical music. In a decisive turn of events in 1877, he made a solemn resolution to alter the course of his life and entered into marriage despite harbouring no inclination towards women. However, this union proved disastrous, leading to a swift spiral into despair. Within weeks, he found himself standing neck-deep in the freezing waters of the River Neva, attempting to bring an abrupt end to his own existence.

It was during his period of convalescence in Italy and Switzerland that Tchaikovsky encountered a turning point, thanks to the patronage of Mme Nadeja von Meck. Her support not only rescued him from financial ruin but also provided the artistic freedom to flourish. Despite newfound success, Tchaikovsky battled lifelong anxiety and depression.

Writing from the depths of his soul, Tchaikovsky infused his music with a profound sense of emotion and introspection, his own personality woven into his music more than most. His intuitive grasp of unity and wholeness shaped his compositions, often leading him to craft pieces from start to finish in a spontaneous outpouring of creativity, sometimes sacrificing meticulous planning and clarity of ideas. Ever the perfectionist, he relentlessly critiqued his own work, driven by an insatiable quest for excellence.

Tragically, Tchaikovsky’s life was cut short by cholera in 1893, a week after commenting that he was less afraid of cholera than any other sickness and proceeding to drink a glass of unboiled water. His musical legacy endures, epitomising the triumph of art over adversity.

The Music

Romeo and Juliet is a tragedy by Shakespeare about two young lovers thwarted by their warring families, leading to their untimely demise. The composer, Balakirev contributed the idea for the ‘Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture’, actually a symphonic poem in sonata form with an introduction and epilogue, and gave Tchaikovsky valuable input throughout the process of composition. Despite the first performance in 1870 being a bit of a flop, Tchaikovsky radically reworked the piece twice so that it finally received the success it deserved at its premiere in 1886.

The motifs describe various themes from the play rather than representing scenes in order. It commences with a serene melody symbolising Friar Laurence who marries the star-crossed lovers, followed by a turbulent allegro thought to describe the feud between the Montagues and Capulets. Next comes the well-known poignant love theme between Romeo and Juliet, changing to a minor key when Juliet discovers too late the lifeless body of Romeo by her side and concluding with a somber rendition of Friar Laurence’s theme.